Tabletop •

Dickens famously wrote one book about two cities. Martin Wallace, on the other hand, topped that by designing two games about the same city. You know, I’d been milling that intro about in my head for days and it sounded way better there than it does when I type it out. Unfortunately, my delete key is broken so it will have to remain as-is [unfortunately, my delete key is broken too, or it would have been destroyed. -ed.].

What I’m trying to get at is that I’ve played London by Martin Wallace. I’ve played it a lot. I’ve played both the first and second editions and I’m going to talk about it after the jump.

London sounds like your typical, economic-heavy Martin Wallace title. In it, you’re gathering Victory Points, but you do so by building and running a city which earns you money and the ubiquitous (in Wallace titles) black cubes. There are also loans. Many painful and tear-inducing loans. In other words, the game has both riches and suffering, the staples of other Wallace economic games such as Steam: Rails to Riches, Brass, Tinner’s Trail, and Automobile.

When you actually break it out and put it on the table, however, it doesn’t feel like a Wallace game. It’s simpler, less complicated [that’s what simpler means, dummy -ed.], and the theme is a bit more abstract than we’re used to. The game begins in London immediately after the Great Fire of 1666 and proceeds through the city’s next 250 years. The players are pillars of the community tasked with rebuilding the metropolis while lining their pockets. Unfortunately, getting rich creates poverty elsewhere, those would be those black cubes were were talking about. Your final score will be decimated if you don’t find ways to limit poverty in the city while simultaneously raking in the cash.

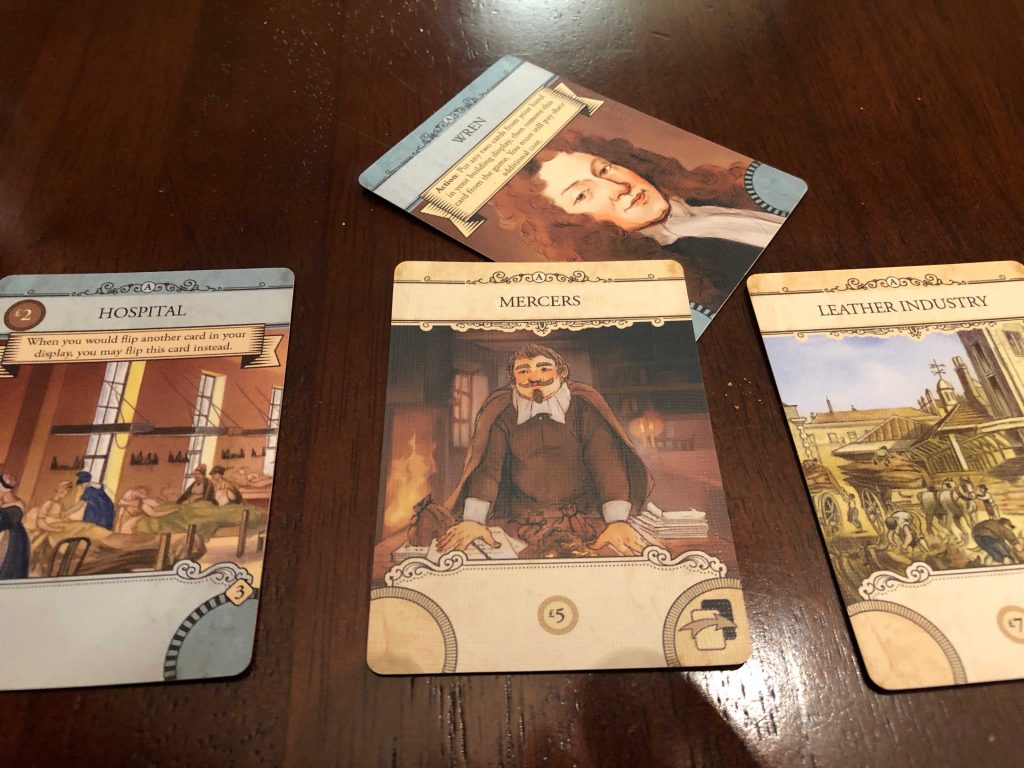

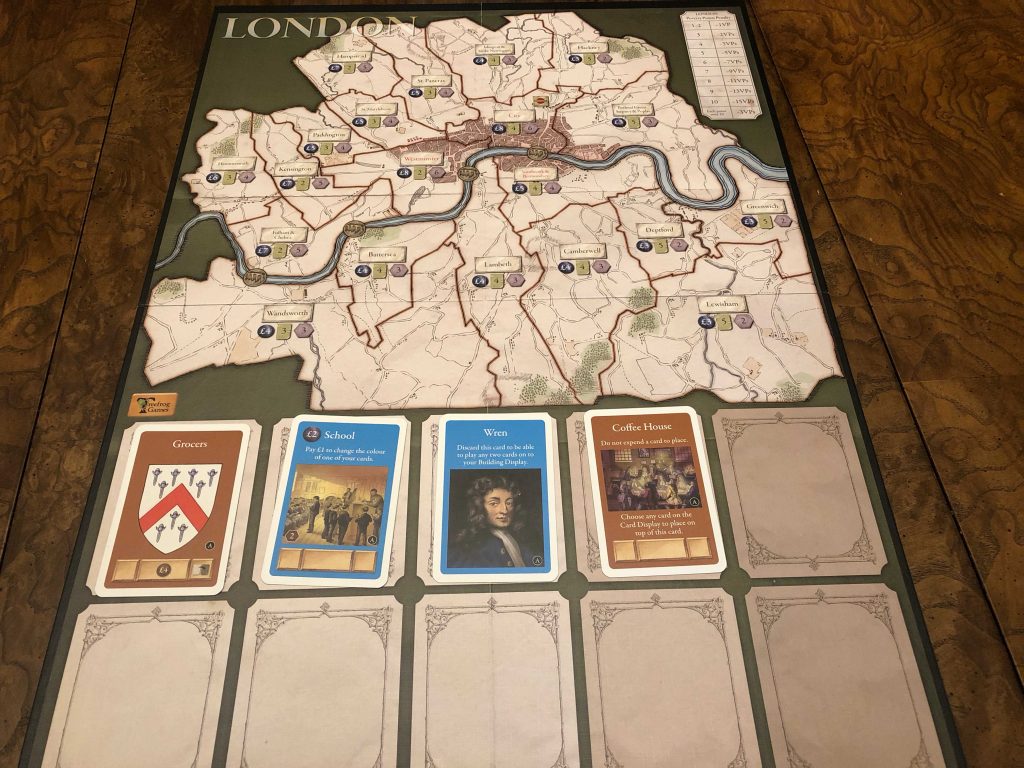

London is a card game and, while both editions have boards, the game is played entirely with a deck of cards that range all the way from Christopher Wren to building the Underground. Each turn you’ll chose one of several actions: build your city, run your city, or buy land. Building your city entails playing cards to your tableau in stacks. You can choose to create a new stack, covering up a previously played building, or start a new stack. Only visible cards will earn you rewards when you run your city, so covering up cards isn’t always a good idea. That said, the more stacks you have, the move poverty you create, so managing your tableau is the heart of the game.

Running your city allows you to activate every visible card in your tableau, earning money or reducing poverty. There are many cards that work well together, so figuring out the combos is how you’ll rack up the most cash. That said, it’s not a CCG and the combos are milder than in most card games, so newbies who aren’t familiar with the deck will not be at a huge disadvantage. The downside of running your city involves the aftermath. Once you earn all your money, you have to calculate poverty and earn poverty cubes which can stack up. You’ll earn cubes for each of your city’s stacks, cards left in your hand, loans, and more. Poverty only affects you in the endgame, so I’ll get back to why this isn’t such a good idea in a bit.

Then there’s buying land, and this is where the first and second editions differ the most. In the first edition, London was represented as a map in which you’d place cubes as you purchased portions of the city, earning that section’s reward. In the second edition, the map is gone and the city is represented by oversized cards, three of which are always available to purchase. When you buy one of these cards, you’ll stack it on top of your previous city cards, and thus only the special power of the top card is active. You still earn rewards when you purchase a city block, but now that each has a special ability (replacing some of the cards you’d find in the common deck in the first edition), picking property has a bit more strategy to it.

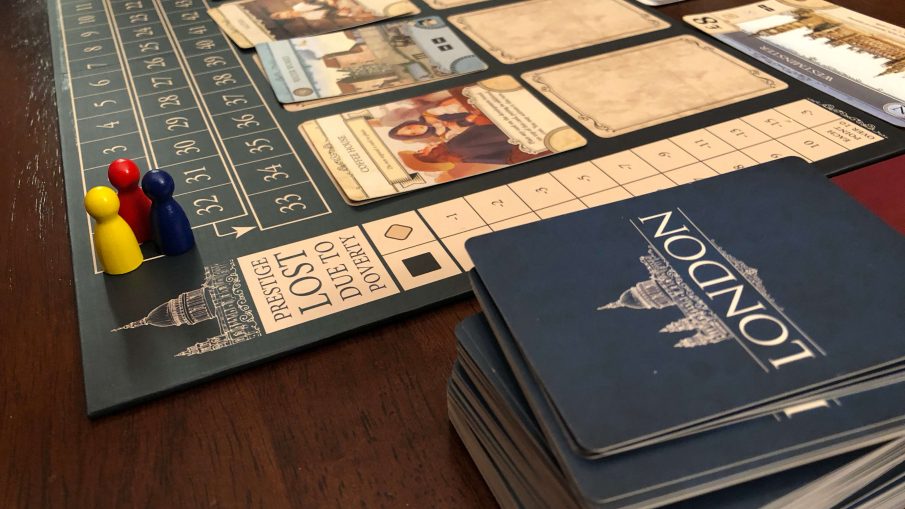

That’s the whole game. Some cards have victory point values on them and, when the common deck is empty, you pick up all the cards in your tableau and add up all the VPs, regardless if the card was buried or visible. If it’s in your tableau, you get the points. Then, poverty is taken into account. Everyone counts up their poverty cubes and the player with the least discards them all. Each other player then discards that many from their poverty total with the remainder being your final poverty level. This number will then tell you how many VPs you lose due to poverty, and the numbers can be staggering. If you have 1-2 poverty you lose only 1 VP, but if you have 10 poverty you’ll lose 15 VP. Every poverty cube you have remaining over 10 is another -3 VP at the end game. You’d assume that it’s hard to rack up that much more poverty than your opponents, but it’s not. Our last game had one player at >60 VPs at game end, only to have poverty and loan penalties take him down to only 4VP. Yes, someone scored only 4VP in an entire game of London.

I just brought up loans, and I realized I haven’t really mentioned them until now. Loans are a thing that you’ll need to deal with in London, as cash isn’t that easy to come by. You can take out loans in £10 increments, but you’ll have to pay back £15 for each. If you’re unable to pay for them at the end of the game (and we always are), it’s -7VP for each unpaid loan. Yes, London likes to kick you in the ass.

London is one of my favorite Wallace games mainly due to the fact that it doesn’t play like anything else. It’s a little bit like Race for the Galaxy, but not really. It feels like a deep, 3-hour Wallace game but is easy to pick up and can be played in 60-90 minutes. If there’s a downside, it’s the disconnect between reality and cardplay. Sure, we’re building stuff but what does “running my city” equate to in the real world? What does each stack equate to, and why do more of them generate poverty? Why do cards in my hand generate poverty? The theme is a good one, and doesn’t feel pasted on, but there is an abstractness that isn’t present in other Wallace titles. There’s history to be found here, but it definitely doesn’t slap you in the face.

The last thing to look at are differences between the first and second editions. The first edition was self-published by Wallace’s now defunct Treefrog brand, whereas the new edition is by Osprey Games. Both games are beautiful to behold, but the new edition has all original art whereas the first edition uses existing paintings and art for the cards. I have to admit that the second edition is the prettier one. The removal of the city map was a big change for a few reasons. In the first edition, you were able to subtract poverty cubes from your tally each time you ran your city based on how many districts you owned. Thus, the strategy was to take out loans and buy as many districts as possible in the early game, thus making poverty a non-factor as you proceeded to build and run your city for the remainder of the game. In the first edition, it was very likely that players would end the game with little to no poverty unless they misplayed it. The new edition removes that rule, and thus there is no easy way to get rid of those black cubes. Poverty is a huge problem that you’re always trying to mitigate through card play as well as buying city blocks that will mercifully let you toss a few cubes back into the central supply. These changes make the game far more strategic and feel much less on rails than the first edition. I’ve played the original edition more than 15 times, and have only played the new edition twice, but at this point I have to say the second edition has won the race and will be the version that lands on the table from this day forward. Any one out there looking to buy a copy of the first edition? I have one that I’m willing to get rid of, cheap.

Yes, much like living in London now. /topical satire

IIRC Osprey published The King is Dead, which is another lovely edition of a very good game.

Not played the second edition of London yet, and my memories of the first are defaced by non-stop complaints about the rats…

Great review! Now I don’t have to write one.

Wallace and taking loans are almost always said in the same breath, so I’m surprised you missed that for so long…

I love the 2nd edition. Haven’t played the 1st, but the 2nd is one of my favourites.